Digitalisation has significantly changed how international trade is conducted, both via the use of digital platforms to facilitate the exchange of non-digital goods and services, as well as through the increase in digitally deliverable exports, including financial and professional services, and mobile apps and content.

The impact of digitalisation of trade is of particular significance to APEC economies which already benefit substantially from cross-border trade. As a bloc, intra-APEC trade in merchandise and commercial services trade grew almost fivefold between 1994 and 2019.1 In 2022, intra-APEC trade volumes reached USD 30 trillion or almost half (47%) of global trade. An earlier study commissioned by APEC found that in 2018, APEC intra-regional digital trade contributed USD 2.1 trillion to economies in the APEC region, approximately 4.1% of regional GDP.

Governments recognise the enormous opportunity presented by digital trade and have taken steps to create a global rules-based system to harness the opportunity. Past research discussed the overall benefits of digital trade participation to an economy, and the importance of digital trade rules in driving digital trade growth.2 However, increasing participation in the digital trade ecosystem also depends on the readiness of the domestic business environment, including businesses and consumers. There is already growing recognition of this, as digital economy agreements (e.g., Digital Economy Partnership Agreement (DEPA) are increasingly going beyond digital trade rules which support “at-the-border” trade liberalisation, to look at how economies can work together to strengthen “behind-the-border” capabilities (e.g., strengthening digital infrastructure or skills) to support digital trade).

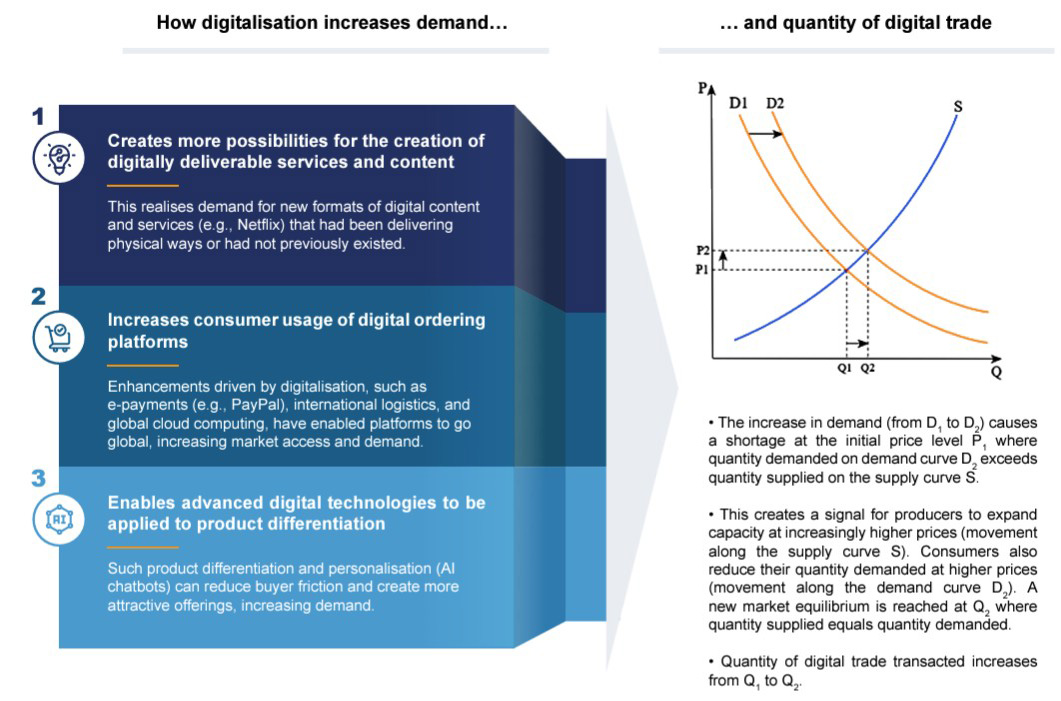

Past research has generally acknowledged that increased digitalisation is beneficial for digital trade participation, given the link between overall digital adoption and the increased use of digital trade tools as well as the ability to produce digital goods and services.3 However, the empirical evidence on the strength of this relationship remains limited, largely due to the lack of sufficiently granular data on digital trade flows. Furthermore, past measures of digitalisation have relied on indicators such as Internet use or broadband coverage. Such data has not been consistently available across economies and sectors, and where available, might not be directly comparable due to differences in collection methods.

This study aims to address this gap in the existing body of literature by using a novel methodology to estimate digitalisation levels among APEC economies. This will allow for a closer study on the extent of digitalisation across economies and sectors as well as support a more in-depth examination of the relationship between digitalisation and digital trade. It relies on the following measures for digitalisation and digital trade:

Digitalisation

The study relies on digital intensity as an approximation for digitalisation. This can be expressed as the share of inputs from digital sectors across all intermediate and capital inputs. Existing studies typically measure digitalisation through digital connectivity indicators such as the extent of Internet access or usage. This is unable to provide a direct indication of the extent to which the business leverages digital tools to improve or transform the process of producing goods and services. Digital intensity captures a more focused perspective of how digitalisation enters the production process through one of two separate input components used in production: (i) raw materials (intermediate inputs); and (ii) machinery and equipment (capital inputs). This provides a more consistent measure of digitalisation across sectors as well as economies and enables analysis to be conducted at the sector-level compared to connectivity indicators which are typically available only at the economy-level.

It is important to acknowledge that this approach has minor conceptual limitations, which have been noted for transparency and to guide future research. Sectors currently classified as producing ‘digital’ products also produce non-digital intermediate inputs, albeit in smaller proportions. Additionally, this methodology does not account for differences in the quality of digital products employed as intermediate inputs, nor does it capture the labour contribution for the in-house development of digital assets.

Digital Trade

This study relies on the definition established in the OECD-WTO-IMF Handbook on Measuring Digital Trade (Second Edition) and leverages the same approach from a previous APEC study (also developed by Access Partnership) to provide an estimate of digital trade.4 Broadly, the methodology recognises that there are two key components that form digital trade.

Component 1 covers goods and services which are digitally ordered but not necessarily delivered through digital means. Examples of such transactions are purchasing a wallet through an e-commerce platform, or booking a hotel stay abroad via an online portal. It also covers digital content such as music, games or mobile applications ordered via digital platform intermediaries. Component 2 covers services that are digitally deliverable but not necessarily digitally ordered. This includes services such as financial services and telecommunications services.

By examining the impact of digitalisation on digital exports for an economy, the research aims to support policymakers in adopting evidence-based approaches to strengthen digital trade participation. It seeks to provide insights into the following areas:

- How does digital intensity differ across economies?

- How does digital intensity differ across sectors?

- What is the impact of digitalisation on digital trade?

Source: APEC